|

| Picture: Apple |

A recent Saturday afternoon visit to one of the last remaining proper record shops in Paris brought me to a startling and disturbing reality: I was surrounded by, well, me.

To a man (and I mean that literally: this was an exclusively XY environment) almost every other punter appeared to be displaying identical physical and social attributes: ill-advised ponytails, paunches (yeah, guilty), fading tour T-shirts, age-inappropriate board shorts (guilty again) and footwear (yup, as charged). This was a parade of the pallid and the varyingly socially inadequate, approaching, in or past their fifth decades, and in one or two cases, getting out only once a week for an intense trawl through the racks of CD and resurgent vinyl.

This is - and I suppose I should accept that I'm a member - a dying breed. Like gatherings of D-Day veterans, its number grows thinner with each year (unlike our midsections). Proud, resillient, stubborn old heads who treat music fairs like archaeological digs, Record Store Day like a religious festival, and dusty, dingy, Championship Vinyl-like emporia for their companionship and matching obsessiveness.

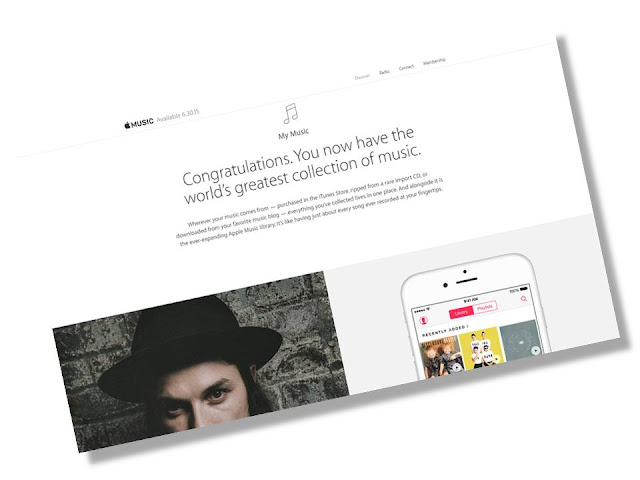

Contrasting with this diasporic scene, earlier this week Apple promised to change "forever" the way we experience music. And they pledged to do so by doing what Apple does best: cloning and apparently improving on other people's ideas.

Monday's opening keynote of the 2015 Apple Worldwide Developers Conference provided a degree of self-serving entertainment for Apple fanboys who enjoy lengthy presentations of "really great" (ad nauseum) and "cool" new features for Macs, iPhones and iPads. On a certain level, it was impressive - there isn't another company in any industry I can think of who can get millions of people to tune in to a webcast to hear about new tech that won't be available for some months yet. More importantly, it demonstrated the might that it can bring to bear on just how we consume our music.

As the finale to the keynote, CEO Tim Cook and his dad-dancing lieutenants (many of whom are in the same age group as the record shop brethren) presented Apple's big new music play, Apple Music, breaking with the Jobs the tradition of 'i'-prefixed things, and also bringing to an end the name iTunes which has been part and parcel of Apple's journey in sound and vision.

In its place came breakthroughs such as...er...24-hour radio, music streaming and an "ecosystem" allowing musicians to communicate directly with their fans. All of which we've seen and heard before (including, in the case of the latter, from Apple themselves - iTunes Ping failed to really take off).

It is true that Apple has enjoyed a long relationship with the music industry. Until 2001, that relationship had manifested itself discreetly as Macs in recording studios (and they're still the computer of choice for musicians in the studio and on tour - hardly a tour goes by where you won't see that illuminated Apple logo shining out from keyboards and mixing desks). But the launch of iTunes on January 9, 2001 changed the relationship altogether between Apple, the music industry and us consumers.

1998's iMac 'Appleized' the concept of a digital home hub and iTunes provided those iMac owners with an easy to use means of organising all those ripped CDs and less then legal downloads; the iPod, launched the following October, formally launched Apple into the world of consumer electronics, eventually leading to the iPhone and subsequently the company becoming the most valuable enterprise in human history.

But in doing so, the constant retooling of iTunes has made it something Apple consumers put up with, rather than love, even though owning Apple hardware is, partly, an emotional communion, a joyous embrace of stunning industrial design and intuitive simplicity. This is no sycophancy: iMacs and iPhones just work. iTunes, increasingly less so.

|

| Picture Apple |

In trying to make it work across and serve different hardware platforms and devices, while adding in the nightmare of digital rights management, iTunes has become, to quote one reporter this week, "a bloated mess". Once, you plugged in your iPod and dragged-and-dropped music onto it. Now, you don't know where to find your music, or how to transfer it, or even how to order it (see Mashable's The 6 Worst Things About iTunes).

In a way, iTunes' evolution from problem-solving simplicity to bloated mess is indicative of Apple's efforts to manage the entertainment industry without actually being in it. The iTunes Store turned music management software for computers into a serious threat to the way the music, film and television industries sell and distribute their wares. Apple - without being a player in content (Steve Jobs got out of that when he sold Pixar to Disney) became agent provocateur, embracing the music and film business while at the same time challenging and even provoking it.

The trouble is that, with music in particular, Apple is simply trying too hard. It's one thing for Jimmy Iovine to call the current state of music "a fragmented mess", and for Trent Reznor to say the world needs "a place where music can be treated less like digital bits and more like the art it is, with a sense of respect and discovery", but it wasn't always this way.

In simpler times, you went to a record shop and bought your music on vinyl, cassette, CD or whatever format was in vogue at the time. You created and curated your collection, enjoying it as much for the tactility of ownership as the self-gratitude of building up a library to reflect and project you.

I agree that squeezing all of that onto cloud servers and hard drives has brought immeasurable convenience, not to mention reducing domestic harmony-threatening "bloke clutter". But that still, to me, feels like closing down a library to make way for a park.

But let's park middle-aged obsession with physical media for now and focus on whether Apple will make any meaningful contribution to the music experience with their new approach, or whether they are just repackaging existing technology - again - and tying it with a bright, shiny bow.

Monday's renaming of all Apple music products under the banner Apple Music, which also launched the long-awaited streaming service to rival Spotify (and finally make use of its acquisition of Dr Dre's Beats Music), plus the radio station and Connect, met with a mixed response.

Internet radio has been in existence for well over 15 years, and premium streaming services have become well established. Spotify now has 20 million people paying $9.99 to access its 30 million-plus library of music, even if very little of that money ends up in the pockets of the artists supplying the music.

After a three-month free trial, Apple Music will come at the same price as Spotify, with much the same size of library, and much the same level of accessibility across different devices and platforms. $9.99 does represent decent value - indeed, a CD a month. Where one might find reason to gripe is that the 9.99 price point applies in all markets - even if that means Britons end up paying $5 more at current exchange rates, and Europeans an extra dollar. But Apple Music's connectivity with social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram and YouTube is a nice, if not exactly essential fan feature, but one notional improvement over Spotify.

I know I'm tilting at windmills over records, films and even books becoming digitised and compressed into slim digital devices, and I know the difference between listening, watching or reading digitally versus the old 'analogue' way is marginal. But what price progress?

Back at the record shop, vinyl is doing well. The old heads are buying it again, hipsters - with their fashion victim sense of irony - are buying them probably for the first time, along with their Klondike miner beards and Penny Farthings.

Vinyl is clearly making a welcome comeback. Thanks, in part, to the annual Record Store Day events, and canny positioning by retailers like HMV in the UK, and its counterparts in other countries, the format is booming. Vinyl sales increased by more than 200% in 2014, and is expected to grow by sales of 2 million units in 2015, with numbers growing amongst 18-to-35 year olds, the so-called sweet spot of consumerism.

|

| Picture: AFP |

In the small Czech Republic village of Lodenice, an equally small local company, GZ Media, is cleaning up having held on to old vinyl-pressing machines. Now, it is pressing millions of vinyl records for the global market. "We pressed around 14 million records last year, the most in the world," sales and marketing director Michal Nemec told the AFP news agency. "Despite the CD boom in the 1980s and 90s, someone with foresight decided to save the old vinyl record presses and store them in a warehouse. A good decision."

Vinyl still represents a fraction of music sales - just 2% - but it's worth noting that few bands these days release new albums without including vinyl in their plans. And it is truly heartwarming to hear how this is holding up. Because even if old heads like me only represent 2%, or whatever percentage of the music-buying public still choosing packaged tunes over streamed bits, it means there are still places in the world where the browsing, choosing, handling and buying of records on a Saturday afternoon as much a part of the reward as getting them home and listening to them.